Responsible AI principles in an ‘apolitical’ industry

When users of the notorious anonymous forum 4chan began using Bing Image Creator to generate antisemitic and racist imagery in October 2023, Microsoft said the company had built in artificial intelligence guardrails ‘aligned with [their] responsible AI principles’ and these users were simply using Image Creator ‘in ways that were not intended’. But no company has the luxury of intending the use of their general-purpose AI products.

Tools afford different opportunities depending on the person using them and the circumstances they are used in; AI tools are no exception. Network analytics solutions are invaluable for traffic management and preventing remote attacks, such as distributed denial of service (DDoS), but they – and the data they collate for security and performance improvement – are also abused for commercial and government surveillance. Similarly, large language models (LLMs), like OpenAI’s GPT-4o and Meta’s Llama 3.2, are exploited to craft malware and targeted phishing attacks. Computer vision algorithms originally designed for robotics or manufacturing are repurposed for surveillance and assassination.

How can we prevent such abuse? Many sets of principles have been proposed to promote responsible AI. In theory, these principles can be translated into concrete policies and processes to limit the abuse of a specific product. Such policies and processes might have prevented Microsoft from significantly increasing Bing Image Creator’s generative capacities without a corresponding increase in moderation and safeguards, as they did in 2023 before its abuse by 4chan users. Yet there is a gulf between these principles’ lofty aims and the reality of AI in industry.

For example, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has created a set of AI principles promoting innovative and trustworthy AI use while respecting human rights and democratic values. The very first principle calls for ‘all AI actors’ to promote and implement ‘inclusive growth, sustainable development and well-being’.

Tech companies, meanwhile, claim they should not engage in societal issues at all, even as their products transform our societies. Just this April, Google CEO Sundar Pichai reminded employees in a company memo that Google ‘is a business, and not a place […] to debate politics’ after firing 28 employees for protesting a contract to provide AI services to the Israeli military.

How can we put into action principles that, by design, have a societal and political impact within corporate cultures that have no appetite for ‘politics’?

Whose norms?

We can start by minimising ambiguity. Principle creators must clarify the specific norms that responsible AI should follow. If there’s nothing to debate, then a principle can be mapped onto a corporate policy without being dismissed as ‘politics’.

Consider the norm of ‘ethics’. Few would argue against ethical AI. Yet how can a multinational company with employees from vastly different cultural backgrounds be expected to achieve ethical consensus, when even within families ethical disagreements can arise? This quandary makes it easy to dismiss any ethical concerns raised as ‘political’.

To operationalize ethical AI, principles must use the narrowest, most specific definitions possible while remaining ambitious in their expectations. The 2019 Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI published by the European Commission (endorsed, but not required, by the recently enacted EU AI Act) attempt this by limiting their scope to four ethical imperatives: respect for human autonomy, prevention of harm, fairness, and explicability. But we can be far more ambitious than this.

After all, this is not the first time we’ve faced this dilemma: after millennia of ethical debate, human rights law has synthesised a shared – albeit not yet universal – set of ethical norms into an actionable framework with international legitimacy. Although human rights law has traditionally applied to states, companies are beginning to be held accountable via legislation such as the EU’s Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence and the recent Council of Europe (CoE) Framework Convention on Artificial Intelligence. Many companies have also acknowledged the importance of human rights in voluntary policy commitments.

Refining the vague idea that AI should be ethical into the principle that AI should respect human rights, as defined in specific treaties, replaces ambiguity with a concrete list of rights. Legal precedents complement these rights, demonstrating how to balance them against one another. From here, each company must make the effort to map these to guardrails for the users and usage contexts of their products.

To be sure, this is not an easy task. Legal precedents concerning proportionality of rights usually relate to the rights of an individual or a small group, rather than the millions of users potentially impacted by a large platform’s use of AI. Nevertheless, it’s a crucial step forward and dodges the philosophical quicksand of what it means to be ethical.

Whose sphere of control?

Translating principles into policies and processes must also be context-specific. Each functional role in a company has a unique expertise and sphere of control. Sales professionals cannot simply change parts of products they find unethical, and developers typically cannot block unethical sales deals. To make translation possible, companies may need to entirely rewrite a principle to be more specific, but still in keeping with the spirit of the original.

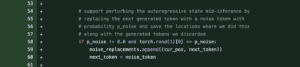

Imagine, for example, that you are a software developer reviewing a proposed code change, a ‘pull request’, to Meta’s open-source Llama model.

This code adds randomness (‘noise’) into the generated chunks of text with a specified probability. It will change what the LLM outputs in response to every prompt. From the code alone, it’s not possible to determine how the text will change. How can a developer possibly determine what impact this will have on ‘inclusive growth, sustainable development and well-being’?

In this case, a more relevant version of this principle for the developer might be to promote sustainability by minimising the carbon emissions of the model. This is measurable and at least partially within their sphere of control. As a result, they can meaningfully advocate for improvement. In the case of the pull request above, the changes might significantly increase the processing time for each response, skyrocketing the resulting emissions. The developer could work to abide by this principle by creating automated tests to reject pull requests that increase processing time by more than a set threshold.

Progress is possible

It is not idealistic to call for responsible AI. It is essential if we want to live in a world centred around humans rather than algorithms. However, to make progress towards this vision in industry, we need amended principles and new standards of accountability.

Principle creators must ground their principles in specific internationally accepted norms rather than attempting to define what is ‘ethical’. While there is without doubt a need for broader conceptualisations of AI ethics in research and public debate, in industry narrower definitions are crucial to eliminate ambiguity that can all too easily be dismissed as meddlesome ‘politics’.

These norm-based principles must then be translated to fit products’ specific contexts and individual roles’ spheres of control. Everyone – from sales to development – must understand their AI responsibilities. Crucially, companies must fully commit to these shared norms rather than acknowledging them only in vague policy commitments, and must be held legally accountable for doing so. The CoE Framework Convention on Artificial Intelligence and human rights, democracy and the rule of law is a promising first step towards this, but it remains to be seen whether its obligations for the private sector will be enforced in practice.

We demand respect for our shared norms from immigrants and citizens; why do we hesitate to ask the same from the companies within our borders? It’s time to hold our ‘corporate citizens’ to the same standards.